MODVEC blog

This is where I ramble on about my views on filmmaking, the process, ideas, discoveries, what I've learned, etc. I'll put up a comment section soon.

January, 2002. After so many short videos, I finally wanted to make my first real narrative. but what to make?

I've always been a fan of heady sci-fi, especially the "sense of wonder" many sci-fi authors create with an ordinary relatable set of characters coming across a huge reality-changing phenomenon.

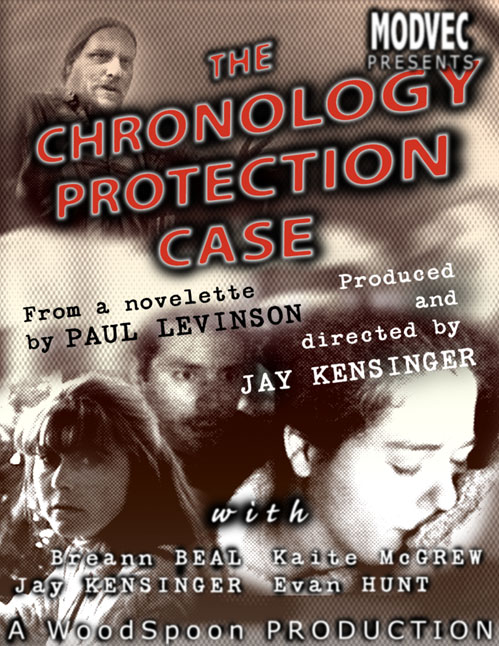

I had enjoyed a lot of the David G. Hartwell edited "Year's Best SF" anthologies, and one of the novelettes--"The Chronology Protection Case" by Paul Levinson--really stuck with me. Short, simple locations, but with an amazing idea that involved the quantum reality of the universe itself. Alright! I had my story! But now I had to adapt it into a screenplay...

A few weeks later I had a screenplay--and I realized a few things: a written story can telegraph a plot twist a lot more directly than a screenplay. What was a gentle foreshadowing in a written story became a huge blaring warning in a film...maybe it was the combination of both audio and visual information...Anyway I had to really make sure I didn't give away the important stuff too soon.

After acquiring a huge plethora of incredible film talent (my friends) I did what turned out to be a smart thing: I story-boarded the entire film, beforehand, shot-by-shot. (See PLAN PLAN PLAN in my blog). Filming went smoothly over a few weeks, with my workplace, house and friends' houses being used for most locations. We got a hospital room through a friend who happened to be a doctor, and we even convinced a police officer to help us with a squad car and officer cameo, as long as we blurred out the insignias (one more advantage of low-resolution media). People like to help with films, especially if you approach them respectfully.

There was a major scene (involving a car accident) that--due to a limited budget--I had to use creativity to realize. Many critics later said it was the best scene in the film (with some saying it was the only good scene in the film).

After my film was shot, edited, and authored to tape and DVD, I had a party and showed it to a bunch of my friends. They enjoyed it, with only a single unintentional laugh--due to my ridiculously overwrought expression in a shot. That shot has since been removed.

I thought then of shelving the film and moving on to my next project...however, my friends and family started suggesting I actually send the film to Paul Levinson, the author of the original novelette. I was pretty scared--what if I get sued or something? I didn't get his permission or anything!

However, I was able to tell my situation to the great sci-fi author Greg Bear at a book promotion event, and he told me to go for it. Well, if Greg Bear says to tell Paul, then what do I have to worry about?

I sent a letter to Paul Levinson, with the consequences of that action described rather entertainingly at the sci-fi review site www.sfrevu.com.

Anyway, Paul--who was kinder and cooler than I could ever have imagined--liked the film, and with his generosity and influence, the film was shown at the I-Con science fiction convention at Stony Brook University on Long Island. It was well received, leading up to a rather disappointing review by www.scifi.com--but the fact that a no-budget sci-fi film was reviewed right next to Sam Rami's Spiderman--budgeted at about $140 million--was pretty cool.

I was able to meet Paul that week and other future visits to New York as well, and found him an amazing person, full of warmth, happiness, and great wit. Paul Levinson--a PhD and the head of Communication and Media Studies at Fordham University--is so much more than a sci-fi novelist: He's authored several books about media and society, and he's the go-to guy for any news program needing an expert on media's influence in modern society (video games, films, tv shows, etc.).

In the wake of the convention, I didn't hear much for a while...when suddenly, Paul leaves a message on my answering machine saying that a friend of his, Mark Shanahan, turned Paul's novelette into a play that used some of my screenplay elements, and the Mystery Writers of America had just given it a prestigious 2003 Edgar nomination for best mystery play.

So we all got Edgar nominations and got to fly to New York to attend the awards ceremony, hosted by a very charming Jerry Orbach.

We didn't win, but I sure as hell thought I had won enough.

If there is any moral to be learned, it is that the kind and generous choices Paul made--when confronted with information about a stranger who turned one of his stories into a film--resulted in a karmic explosion of good fortune for everyone.

UPDATING AND CONVERTING "THE CHRONOLOGY PROTECTION CASE"

One of the issues with CPC is that the film was never meant to be sold or used for profit; it was a simple filmmaking exercise. Then the movie was shown at a few conventions, took on a life of its own, and helped to get Paul, Mark Shanahan and me a 2003 Edgar nomination, so we decided to see if we couldn't put in on a few movie-viewing sites like Netflix.

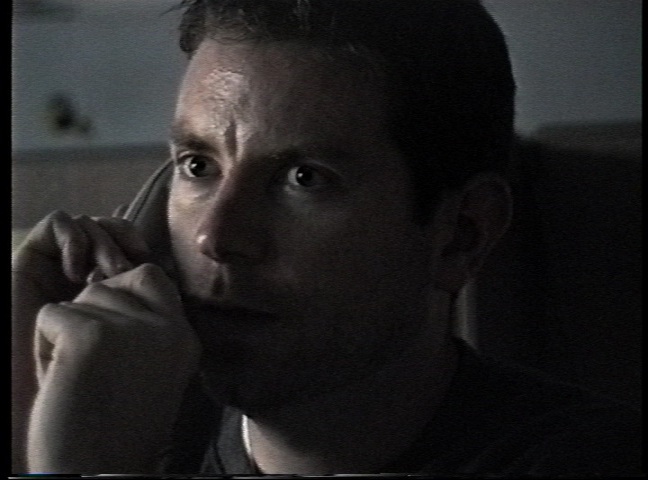

First problem: Copyrighted music, logos, etc. so, a few changes needed to be made. I started to replace the background music, blur out some logos or re-frame some shots, and then I had an idea. I was never happy with the interlaced 30-fps "video" look of the film, a consequence of the inexpensive Hi8 video I had to use:

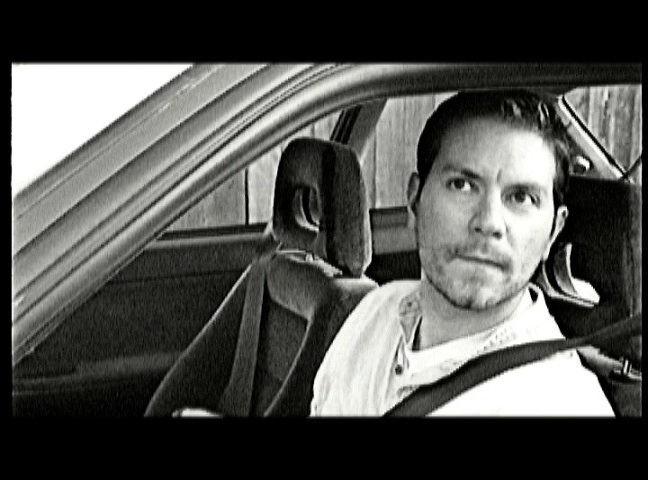

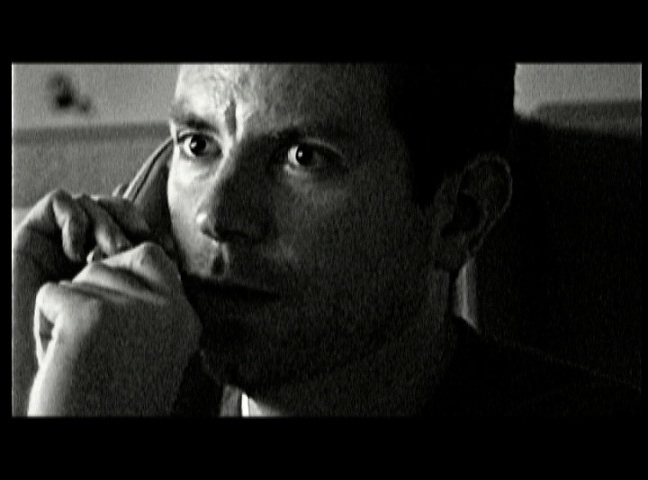

I tried a few different looks in Final Cut Pro, and then had a revelation: What if I just got rid of all the color information? Hi8 video (and miniDV) both use a lot of data to store the luminosity (black and white) information anyway; and I wasn't using color to convey any metaphor or story aspect. So I not only de-saturated the image, but cropped the frame to a more film-like proportion and also changed the frame rate to a more film-like 24 frames a second.

I was astounded at the images I got:

Granted, not the greatest resolution, but the depth of light contrast made up for the graininess of the image.

Anyway, the film I had now looked like an old 60's film-noir, and it made the story, characters, acting and tension even more powerful than before. I've always been a fan of black and white film--most of the photography I do is black and white--and now I had my own black and white murder mystery. It even seemed to go better with the poster I created for CPC many years ago...

ANALOG VS. DIGITAL, RECORDS VS. CD'S

I also discovered another thing about Hi8 video versus miniDV--even though miniDV has the "superior" resolution and image information, the Hi8 video--which is still analog magnetic particles on tape--produced the superior image when converting to black and white. The graininess was still an analog grain, making the medium look like old 16-mm film. Test-conversions of my later miniDV films kept revealing the unyielding walls of digital ones and zeros--I couldn't push the image like I could with the Hi8 data.

I have an audiophile friend who swears by the "flavor" of analog LP records; and while his records can't physically reproduce the volume and frequency range of CD's, I would agree that in most cases a pressed record's actual sonic authenticity--especially on a good system--is superior to CD's. Listening to a record of the jazz masterpiece "Kind of Blue" on an expensive tube audio system is a revelatory experience.

This "analog" argument is becoming weaker and weaker, however, with the unfailing advancement of digital technology: Converting the images from my Canon t2i DSLR to black and white definitely produces some nice results...

A FINAL UPDATE

After I showed Paul Levinson the updated, copyright-free, black and white film-noir version of CPC, Paul had one more suggestion...It was a brilliant idea and would involve something that the vast majority of films couldn't do--but we were in a position to do it. And that's what we're working on now--hopefully it will be finished soon...

JUST MAKE YOUR FILM

Here's the most important advice for anyone wanting to make films. Just make your stupid film. Don't wait forever for the perfect actor--set a deadline. Don't wait for the "perfect" set or location; just rewrite your story. The message and controlling idea is the most important thing! I have too many friends who are still "pulling things together" to complete their film; they are years behind schedule. I'm on my sixth film, and each film I make sucks less and less! And now--finally--I got my first film into a festival, and I got sent that cool laurel wreath png file that I can plaster across my movie poster.

One of the best quotes about filmmaking--or any other creative endeavor--is "Professionals work on bad days". You want to make films because you have a calling, or just love the process, or whatever. But often it doesn't matter how much you love making films; sometimes you just don't want to work on them that day, or that week. Well, sometimes you have to just do it when it's the last thing you want to do. The ones who will only work on a film when they feel like it, or are inspired, or whatever, will spend the next years watching the completed films of the people who worked on them when the last thing they wanted to do is get up at six in the morning to spend the next 18 hours shooting, organizing, compromising, and pushing forward. So make your stupid film. Force yourself! It's like getting in shape or building a house. Make deadlines! Schedule film shoot days even if you don't have everything done--It will force you to complete your work 'cause you don't want to disappoint anyone.

PLAN PLAN PLAN

Storyboard every shot, not just the key shots. Draw the entire film as a comic. My second film, "American Ghost Story" had 1300 panels--not great drawings, but it was understandable enough so that I never arrived at a location with twenty people waiting for you and thought, "Okay, how am I going to shoot this?" You don't have to follow to the letter what you drew, but at least you'll always have a starting point for the shot setup that you can change on the set if you get more inspired.

Organize the camera placement! If you're doing a one camera shoot (and you probably are) then determine what shots of a multiple shot scene share the most proximate camera locations; then shoot the grouped camera proximity shots together to save even more time.

Once, for my third film "Jenny is Alone", we had to complete about 50 shots in a make shift "classroom", organizing 15 school kids and four costume changes for the leads--knowing we had only a few hours before we had to give back the room at the community center. We simply didn't have time to "figure out" the best place for the camera--we had to know where the camera would be so we could go through the shots as quickly as possible. So we storyboarded the entire film, "filming" it virtually on paper. We were able to get every shot we needed.

DO IT YOURSELF

Don't have millions of dollars? Then you're going to have to learn a lot of stuff. Most of it's really interesting.

Learn writing: It's all about the story. Write one. Have your friends tell you why it sucks, and tell them to be brutal. Or pick a really good short story for your first practice film--Something that excites you. Read "Story" by Robert McKee.

Learn directing: Get some friends and direct them in a short scene. Read theatre books about general blocking and cinematography. Read "Directing Actors" by Judith Weston.

Learn acting. Really, one of the biggest complaints that actors have about directors is that the they don't know anything about the thought processes of an actor. Your actors, and the story itself, are the most important things in your film. Get involved in community plays. Read "An Actor Prepares" by Stanislavski (There's a reason actors always talk about Stanislavski).

Learn filming: Take lots of pictures. Learn composition, the rule of thirds. Read books about cinematography, and see the amazing 1992 documentary "Visions of Light" in a theater or on a really good TV.

Learn filming: Take lots of pictures. Learn composition, the rule of thirds. Read books about cinematography, and see the amazing 1992 documentary "Visions of Light" in a theater or on a really good TV.

Learn editing: Use Final Cut Pro, Adobe Premiere, etc. Film a short dramatic scene and see how you can change the tension, humor, and even the objectives and emotions of the characters just by cutting in different places. Read "In the Blink of an Eye" by Walter Murch.

Learn editing: Use Final Cut Pro, Adobe Premiere, etc. Film a short dramatic scene and see how you can change the tension, humor, and even the objectives and emotions of the characters just by cutting in different places. Read "In the Blink of an Eye" by Walter Murch.

Learn sound: You've probably heard it before that indie filmmakers can get away with bad visuals but never amateurish sound. It's true. Get a good shotgun microphone, practice recording dialogue. Listen to sounds at different distances and in different rooms, and learn a program like Soundforge to understand reverb, equalization and other sound processing so you know how to change a recorded sound to fit a scene. Use Garage Band or Cakewalk to get used to tracks and panning.

Learn visual effects: This is the key knowledge that can add a few virtual zeros to the end of your film budget and make it stand out from the other films (provided it's still a good story with great performances and technical competence). Buy books on Adobe After Effects and learn how to composite. Learn a 3-D modeling program like Lightwave 3D, and teach yourself how to composite in 2D and 3D with programs like Syntheyes so you can create virtual sets. Visual effects are fun, and you can use the visual medium of film to manifest ideas in a visually astonishing way as long as you always ground yourself in reality and don't go overboard with the effects. (More to come on that later.)

Learn visual effects: This is the key knowledge that can add a few virtual zeros to the end of your film budget and make it stand out from the other films (provided it's still a good story with great performances and technical competence). Buy books on Adobe After Effects and learn how to composite. Learn a 3-D modeling program like Lightwave 3D, and teach yourself how to composite in 2D and 3D with programs like Syntheyes so you can create virtual sets. Visual effects are fun, and you can use the visual medium of film to manifest ideas in a visually astonishing way as long as you always ground yourself in reality and don't go overboard with the effects. (More to come on that later.)

And remember: Never think you're an expert in anything; always be in a continual process of learning. Take advice from everyone; you will always learn more from brutal criticism than friendly compliments (although those are always nice). Know that, as an indie filmmaker, you sometimes have to settle with your own incompetence to complete a film.